A bombshell report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) in January 2024 exposed that the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) routinely “share and receive domestic violent extremism threat-related information with social media and gaming companies.”

According to the GAO, DHS activities include gathering and sharing intelligence from and to social media and gaming companies: “shar[ing] information with [the DHS Office of Intelligence and Analysis] I&A about online activities promoting domestic violent extremism…”

It’s like something out of George Orwell’s 1984: “Big Brother Is Watching You!”

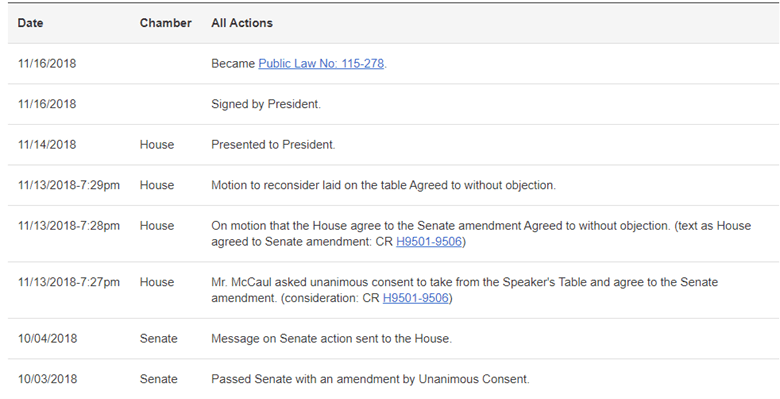

But what is lesser known is that Congress authorized it — unanimously.

In 2018, in the closing days of the Republican-controlled House on a voice vote and in the Senate on unanimous consent, H.R. 3359 authorized the Secretary of Homeland Security, and the then-newly created Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) to gather and disseminate information to the private sector including Big Tech social media companies in a bid to combat potential foreign and domestic terrorists.

The law authorizes CISA to gather intelligence from “private sector entities” including social media and gaming companies, and to coordinate with other agencies, including the FBI: “To access, receive, and analyze law enforcement information, intelligence information, and other information from agencies of the Federal Government, State and local government agencies (including law enforcement agencies), and private sector entities, and to integrate such information, in support of the mission responsibilities of the Department and the functions of the National Counterterrorism Center established under section 119 of the National Security Act of 1947 [50 U.S.C. 3056], in order to… identify and assess the nature and scope of terrorist threats to the homeland;…detect and identify threats of terrorism against the United States; and … understand such threats in light of actual and potential vulnerabilities of the homeland.”

The law also allows CISA to distribute that intelligence to “private sector entities,” including social media and gaming companies, and other government agencies: “disseminate, as appropriate, information analyzed by the Department within the Department, to other agencies of the Federal Government with responsibilities relating to homeland security, and to agencies of State and local governments and private sector entities with such responsibilities in order to assist in the deterrence, prevention, preemption of, or response to, terrorist attacks against the United States.”

Read that again. This is all to “assist in the deterrence, prevention, preemption of, or response to, terrorist attacks against the United States.” So, when the government invokes this authority to censor or gather intelligence on social media or gamers, the officials doing so have to show they are targeting domestic terrorism, of course, without any judicial review or due process.

And not a single member of either the House or Senate of either party objected to it. Not one. Then-President Donald Trump signed the legislation, which tragically ended up being used to censor Republicans and conservatives in 2020 and beyond, including objections to tyrannical Covid lockdown policies, the Hunter Biden laptop story, concerns about mail-in ballots and legal challenges raised by the Trump campaign after the election.

The Jan. 2024 GAO report confirms exactly how the new law and agency were used explicitly to gather and share intelligence from and to social media and gaming companies.

Specifically, the intelligence gathering and sharing is done via meetings and electronic communications, according to the report: “In April 2023, [the DHS Office of Intelligence and Analysis] I&A attended Extremism and Gaming Research Network’s monthly meeting and provided a briefing on an intelligence assessment product about domestic violent extremists’ use of video gaming adjacent platforms. According to officials, I&A can also email intelligence products to representatives from these organizations.”

As for the FBI, they are set up to receive tips from gaming companies about potential domestic extremist threats, according to the report: “The National Threat Operations Center (NTOC) has been the FBI’s centralized tip processing center since 2018. Members of the public, including officials from private sector entities, can submit tips to the FBI via NTOC. Four companies told us that when they identify a potential domestic violent extremist threat on their platform, they report the incident to the FBI for possible further investigation. NTOC processes the tips, conducting an initial evaluation and forwarding some tips to FBI field offices for further action, such as opening an investigation.”

When it comes to the domestic gathering and sharing of intelligence, the FBI coordinates that with DHS in a joint venture: “The FBI provides briefings, awareness webinars, and other informational materials to Domestic Security Alliance Council member companies on a variety of threats to U.S. critical infrastructure, including domestic threats. One company told us this partnership is useful in providing frequent updates on domestic threats, such as intelligence briefings and email digests.”

It includes joint intelligence products distributed to social media and gaming companies: “The FBI and DHS have issued joint informational products related to the online threat landscape. For example, NCTC, the FBI, and DHS issued a booklet on violent extremist mobilization indicators in 2021, as well as a spin-off booklet on the tech sector in 2022.”

However, the legislation was not the beginning of government efforts to target social media and gaming companies but rather the culmination of some of those efforts.

In 2012, DHS launched a program to create data analytical tools for gaming consoles because gamers might not use dedicated game chat software and opted to use in-game chats: “each gaming system platform uses its own proprietary architecture, software, and communications protocols.” In conjunction with the Navy, DHS used consoles purchased overseas with non-U.S. person data, and then they figured out how to get the data out of them, and then published the methodology open source for law enforcement for intelligence gathering and criminal investigatory purposes.

According to the DHS description, “The Gaming System Monitoring and Analysis project is a research effort funded by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Science and Technology Directorate (S&T) Cyber Security Division (CSD) to design and develop forensic tools for extracting data from gaming systems.”

The program dates back to 2008: “In 2008, DHS S&T was approached by the law enforcement community for assistance in researching a capability to investigate potential crimes being conducted through the use of modern gaming systems.” It led to the U.S. Navy being recruited to do the work: “The Naval Postgraduate School (NPS) was selected by DHS S&T to complete this work because of its related expertise in the area—specifically the development of the Real Data Corpus (RDC) and its experience in developing open source tools for bulk data analysis. DHS S&T is funding this effort to research and develop forensic tools that can support law enforcements efforts to investigate game consoles and similar electronic devices.”

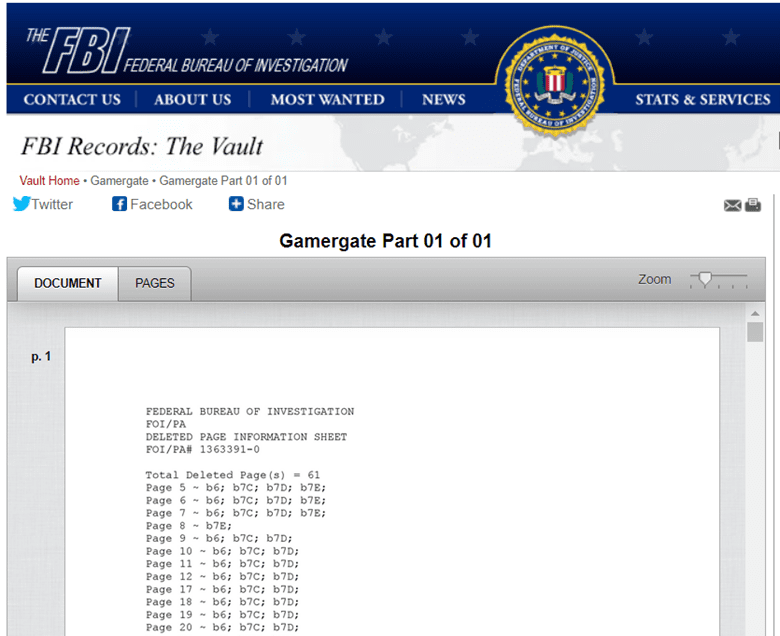

In a similar vein, in 2014 and 2015, the FBI officially investigated Gamergate, specifically related to death threats made against Anita Sarkeesian. In 2017, the agency released its investigation files for public review. Ultimately, no prosecutions were brought, and some individuals were given warnings.

Commenting on the report to the Verge, Brianna Wu stated, “All this report does for me is show how little the FBI cared about the investigation… As I remember, we had three meetings with the FBI, we had two meetings with Homeland Security, we had three meetings with federal prosecutors in Boston. Almost nothing we told them is in this report.”

Government monitoring of supposed violent extremism in gaming would not end there. In March 2021, DHS’s Office for Targeted Violence and Terrorism Prevention (OTVTP) hosted its 6th Digital Forum on “the risks of radicalization to violence through online gaming platforms, but it also emphasized how the gaming industry and civil society are best positioned to create solutions together.”

In 2022, DHS awarded $700,000 to Middlebury College to conduct surveys of game developers and gamers for “Financial Assistance for Targeted Violence and Terrorism Prevention”.

According to the DHS website, awarding the grant included “development of… centralized resources for monitoring and evaluation of extremist activities”: “This joint project from the Center on Terrorism, Extremism, and Counterterrorism, Take This, and Logically seeks to develop a shared framework for understanding extremism in games. This includes the development of a set of best practices and centralized resources for monitoring and evaluation of extremist activities as well as a series of training workshops for the monitoring, detection, and prevention of extremist exploitation in gaming spaces for community managers, multiplayer designers, lore developers, mechanics designers, and trust and safety professionals.”

And it should surprise no one that in 2022, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) published a comprehensive report on the topic, “Hate Is No Game: Hate and Harassment in Online Games 2022,” that claimed “one in ten gamers between ages 13 and 17 had been exposed to white-supremacist ideology and themes in online multiplayer games.” The ADL often coordinates and is used as a source by DHS in gathering open-source intelligence on supposed domestic extremists.

In 2022, DHS released another report, “Countering Foreign Malign Social Network Manipulation in the Homeland – Emerging Trends: Technologies, Tactics and Techniques,” that highlighted an effort by “right-wing extremist groups” to recruit children that stated, “As misinformation spread and radicalization evolved, right-wing extremist groups have taken to recruiting, training, and communing with users as young as 13 years old on popular gaming platforms. These country agnostic spaces leverage memes and code phrases to circumvent content filters and censors; i.e. ‘commit not alive’ to refer to suicide or murder. Most of the children and adults who are exposed to these channels are either already radicalized or quickly become so off-platform in search of community. Some of the longest, most entrenched extremist groups exist in channels on the popular gaming platform Steam, where they have a wide chance of exposure. Most have not been removed from Steam because they conduct radicalization off-platform, but initial vetting on Discord channels often includes ideology questionnaires and ‘skin color checks’. Extremists ‘offramp’ vetted prospects to blogs, encrypted messaging, and ‘alt-tech’ social media platforms that either cannot intervene to prevent the promotion of hate speech or extremism due to lack of a centralized control or visibility or will not intervene due to adherence to an absolutist vision of free speech or outright support of the extremist ideologies.”

These are just a sampling of the efforts by the federal government to target gaming companies, gamers and social media for censorship, surveillance and intelligence gathering.

Again, the common thread that ties these efforts was the 2018 CISA counterterrorism law that passed Congress unanimously.

The law allows DHS to coordinate with other federal agencies and “private sector entities” to gather and distribute intelligence “to assist the deterrence, prevention, preemption of, or response to, terrorist attacks against the United States.” The breadth of this might be terrifying to some, but given the body of research the government is engaged in, and the number of years this has been going on, including figuring out ways to break into consoles going back to 2008, it should not at all be surprising that it continues.

But this all could be facing a significant challenge at the Supreme Court this year in the pending case Murthy v. Missouri. That case will determine, according to ScotusBlog: “(1) Whether respondents have Article III standing; (2) whether the government’s challenged conduct transformed private social media companies’ content-moderation decisions into state action and violated respondents’ First Amendment rights; and (3) whether the terms and breadth of the preliminary injunction are proper.”

According to the Jan. 2024 GAO report, DHS and FBI had to contend with the injunction by the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Louisiana, issued July 4, 2023, which appeared to block these efforts from continuing: “The preliminary injunction prohibited multiple defendants, comprised of several federal entities and named individuals sued in their official capacity, from coordinating and communicating with social media companies in a way that would infringe upon U.S. citizens’ constitutional right to free speech, such as seeking the removal or suppression of content containing protected free speech.”

As a result anything that might pertain to the injunction is first run through the agency’s counsel: “In July 2023, [the DHS Office of Intelligence and Analysis] I&A officials told us they continued to consult counsel prior to engaging in activities that could fall within the scope of a preliminary injunction that was issued pursuant to ongoing litigation in Missouri v. Biden.” Missouri v. Biden was folded into the Murthy v. Missouri case.

Similarly, the FBI is said to exercising caution in light of the rulings: “the FBI continues to proceed cautiously, adding an additional layer of review and approval by the FBI Office of the General Counsel with respect to certain communications with social media platforms.”

At the time, the scope of the injunction was any activities by the government “urging, encouraging, pressuring, or inducing in any manner the removal, deletion, suppression, or reduction of content containing protected free speech posted on social-media platforms…”

In other words, even though the injunction said these agencies could not engage with social media and gaming companies to censor content, DHS stated they would just check with their attorneys before doing so: “they continued to consult counsel prior to engaging in activities that could fall within the scope of a preliminary injunction.”

Same with the FBI, which said it was using “an additional layer of review and approval by the FBI Office of the General Counsel” for those activities enjoined.

Again, the only thing that was enjoined was “urging, encouraging, pressuring, or inducing in any manner the removal, deletion, suppression, or reduction of content containing protected free speech posted on social-media platforms…”

Since that time, the U.S. Supreme Court has stayed the injunction against the companies and so, according to GAO, DHS and the FBI are “no longer limited by this case from interactions with social media companies,” with a ruling in the case expected later this year.

Undoubtedly, the Supreme Court will have to contend with the precedent set out by the Brandenburg v. Ohio Supreme Court decision of 1969 which found “the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.”

And that was a case of white supremacists who in demonstrations were in fact advocating the overthrow of the government, however, as there was no actual attempt to do so, was protected political speech. Again, just because speech might be disrespectful or deemed by government agencies to be extremist does not give the government the power to do anything about it if it is not resulting in imminent lawless action.

As George Orwell, a socialist who was warning against communist totalitarianism in his novel, 1984, wrote, “It’s a beautiful thing, the destruction of words.”

In the meantime, the spying and censorship is still continuing, albeit under the watchful auspices of department and agency legal counsels. And this being overturned by the Supreme Court is by no means guaranteed, with years of abuse by fearful government officials who believe they’re under threat.

So, if you’re an online gamer who is suspicious of government authority, as the saying goes, perhaps just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they’re not listening.

Robert Romano is a contributor to the Fandom Pulse and the Editor-in-Chief of Comicsgate.org.

Yuri Bezmanov and George Orwell were right.